Black Gold: The Real Consortium

"Billions of dollars, funneled over the last six months alone. But to fund what?"

In the past two editions of the Black Gold series, we explored the history of the American elites' covert international financial network based on looted assets funneled through banking institutions around the globe after World War II. We also examined comments from the legendary attorney Danny Sheehan about the origin of the UFO cover-up, shedding light on the dynamic between the United States government and the wealthy "robber baron" families that put their fingers on the scale of policy to benefit themselves.

We then scrutinized aspects of this network that may have had an influence on our sciences and understanding of human history by installing career intelligence officials to head up institutions like the Smithsonian Institution. We also investigated instances of American intelligence services using scientific studies as cover for more nefarious activities like biological weapons testing and even MKULTRA.

As extensive as these inquiries may seem, there are still countless questions that have gone unanswered. Although this tangled web of covert finance may still be hidden from public view, the effects of its corruption can be felt today more than ever.

To that end, this article will explore the evolution of this system in more recent years. Through rampant consolidation of defense contractors, along with the revolving door of officials between the Pentagon and private industry, the political slush fund approved by Truman after the war has become a behemoth even Congress cannot penetrate.

Before diving into the specifics, however, let's set the stage with a roadmap we can use to navigate this unrelenting labyrinth that only an army of forensic accountants would be able to make sense of.

A Helpful Roadmap

One aspect of the fiction series Sekret Machines that is somewhat unique among the literature of UFO lore is the involvement of a private financial entity in the reverse engineering of these anomalous craft. Although this series is indeed fiction, the general ideas brought to light within them are informed by the extensive experience of the authors' government advisors who held high positions of power within the US defense establishment.

This "fictional" organization, called the Maynard Consortium, is portrayed as a kind of government all to itself, conducting intelligence and military activities along with its normal everyday business obligations. When one of the board members dies after an agent of the corporation forces him to jump off his balcony at gunpoint, his daughter Jennifer assumes his position on the board, blissfully unaware of the sordid practices used to put her in that position.

As Jennifer reviews her father's financial dealings, she grows concerned about what her father may have been involved in. Money was moved between countless bank accounts all over the world. Countries known for human rights violations were the beneficiaries of massive payments from Maynard's funds. Weapons and aerospace companies received backing in nations not known to possess the kinds of programs described in the records.

The Maynard Consortium had a snappy website, brochures, and interminable files detailing its various accounts and investments, but it all seemed to end in cascades of numbers. What they were actually investing in was anybody’s guess.

The numbers were not exclusively misleading, however. Whatever that aerospace investment was, it was expensive. Billions of dollars, funneled over the last six months alone, but to fund what? Even her father’s laptop had been unable to shed light on that.

“These files make no sense,” she remarked to Deacon as she pored over them. “Most of the directories are empty, and the accounts they do show explain only about a tenth of the funding.” She sighed and then whistled. “Nigeria has a space agency? And Saudi Arabia? This is weird.”

Deacon materialized at her shoulder.

“Maynard is funding the Nigerian Space Agency?” he asked.

“And the Sri Lankan Space Agency, if you can believe that. And the ones in Bangladesh, Tunisia, and Pakistan. That’s a pretty strange list of bedfellows, even without the space agency bit.”

“But the funding levels are low,” Deacon mused, peering at the screen.

“So where is the rest of it going? And why can’t we see it?”

A bit later on, Jennifer finds a thumb drive her father had hidden. However, the data contained on it raised even more questions about the corporation's business practices.

Some of the names in the files were not companies. They were people, individuals in a variety of professions and places, which simple online searches quickly revealed: English lawyers, German financiers, Russian industrialists, even one US Senator who she remembered visiting Steadings when she was an adolescent. A “friend of her fathers.” They probably all had ties—of some sort—to SWEEP, whatever that was, and none of it had shown up in any of the Maynard group’s records or files or—for that matter—their boardroom discussions.

Whatever this "SWEEP" entity was, it seemed very important to the international money transfers that the Maynard Consortium were involved in.

The companies and their assets were always global, scattered across the world but seemingly unconnected, and they tended to melt away after a few years. Until SWEEP appeared in 1964. It looked like it grew out of a conglomeration of previous corporations, though the historical record was so tangled at this point that she couldn’t be sure.

It seemed to quietly swallow up the other companies, until it was moving hundreds of billions of dollars, pounds, euros and other currencies through the Caymans and Seychelles, through Liechtenstein, Vanuatu, Belize, and Singapore.

As I stated previously, this series of Sekret Machines books is what the authors refer to as informed fiction, the result of meetings and consultation with advisors in possession of deep knowledge spanning decades of working within the military-industrial complex.

That in itself likely makes the investigation of potential real-world versions of these narratives worth our time, and we will do so throughout the rest of this article, starting with the financial organization referred to as "SWEEP."

An International System

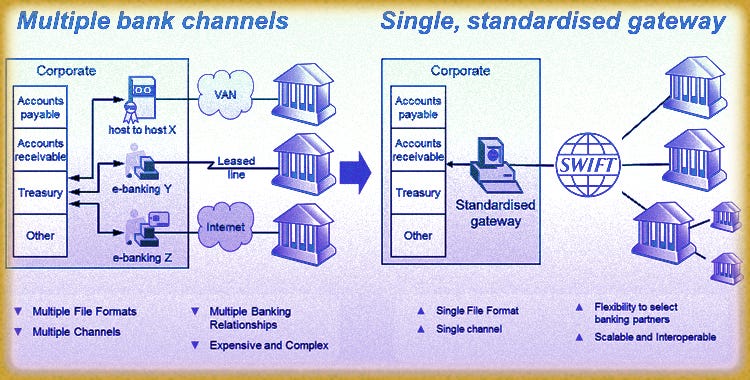

One of the most important aspects of this covert international financial network is the mechanism that allows it to exist and maintain its transactions. When reviewing the characteristics of this fictional "SWEEP" organization I realized that many of them line up with the history and functionality of the international banking system called the Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunication — or as it is more commonly known by its acronym, SWIFT.

The Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunication (Swift), legally S.W.I.F.T. SC, is a Belgian cooperative society providing services related to the execution of financial transactions and payments between certain banks worldwide. Its principal function is to serve as the main messaging network through which international payments are initiated…

The Swift messaging network is a component of the global payments system. Swift acts as a carrier of the "messages containing the payment instructions between financial institutions involved in a transaction". However, the organisation does not manage accounts on behalf of individuals or financial institutions, and it does not hold funds from third parties. It also does not perform clearing or settlement functions. After a payment has been initiated, it must be settled through a payment system, such as TARGET2 in Europe. In the context of cross-border transactions, this step often takes place through correspondent banking accounts that financial institutions have with each other.

As of 2018, around half of all high-value cross-border payments worldwide used the Swift network, and in 2015, Swift linked more than 11,000 financial institutions in over 200 countries and territories, who were exchanging an average of over 32 million messages per day (compared to an average of 2.4 million daily messages in 1995).

In recent years, the financial services firm has been in the news in the context of sanctions against Russia for its activities around the globe, with some Western leaders calling for the entire country to be cut off from using the transaction messaging system. Russia was finally cut off from the service after its invasion of Ukraine last year.

The use of SWIFT as a last resort in the context of sanctions is a testament to the importance of its service to the entire international banking structure. In other words, if a solar flare were to take out the technology these transactions depend on, it's fair to speculate that the world economy could potentially come to a grinding halt.

Besides the obvious "coincidence" of the acronyms "SWIFT" and "SWEEP" both containing five letters — of which the first two are the same — the history appears to line up as well.

Throughout the history of banking, the boundary between competition and cooperation has had to be navigated; in the case of SWIFT, support for a shared network slowly gained momentum and began to achieve institutional form.

The earliest available evidence for this is in the late 1960s, when the Société Financière Européenne (SFE), a consortium of six major banks based in Luxemburg and Paris, initiated a ‘message-switching project.' By 1971, there was sufficient interest to generate sponsorship from 68 banks in 11 countries within Western Europe and North America for two feasibility studies to examine ‘the possibility of setting up a private international communications network'…

What is remarkable about the early history of SWIFT is that a “society” founded by a relatively small number of banks to reduce errors and increase efficiency in inter-bank payments, evolved into a broader industry cooperative and became an unexpected network phenomenon.

The notion of a network effect was not part of the consciousness of those involved in the original SWIFT project during the 1970s. Their focus was solely on creating an entity, a closed society, to bind members together in an organizational form that would enforce standards designed to create efficiencies in transactions between the member banks.

The use of the phrase "closed society" as the original objective of SWIFT is quite interesting, and brings to mind the "breakaway civilization" hypotheses promoted by authors like Richard Dolan and Joseph Farrell. The fact that such a close-knit group of banking institutions was at the inception of this cooperative may lead one to wonder if these original members could have insulated themselves inside the system as it expanded, with each additional layer of seemingly legitimate growth providing the ability for more potential obfuscation of funds.

Given the international nature of the money recipients by the fictional Maynard Consortium in Sekret Machines, and the insinuation by Jennifer that "they probably all had ties—of some sort—to SWEEP," I think the SWIFT banking system is likely the leading contender for the organization being referred to in the series.

But now that we've established the most likely candidate for the mechanism that moves the money around, let's now turn to the possible real-life organization that could be represented by the Maynard Consortium.

Private Compartmentalization

As I've stated previously, one of the major factors that establish the Maynard Consortium as something more than just a banking organization is the extensive ties they appear to have within the covert world of international espionage. One of the main characters, named Morat, conducts mercenary missions on Maynard's behalf. The prevalence of doctors and scientists involved in these same activities under the employ of the Consortium suggests a private intelligence firm may be one of the company's subsidiaries.

After researching some of the largest conglomerates in the world and comparing relationships to the defense sector throughout the past decades, one of them stood out, particularly in the context of the UFO cover-up. Although the Maynard Consortium portrayed in the Sekret Machines books is a British corporation, I believe the international finance aspect of this scenario and the fictional nature of the series certainly allows for the possibility that they represent an asset management company based in the United States.

The organization that kept popping up time and time again throughout my research is a massive private equity firm with deep ties to the defense establishment known as the Carlyle Group.

Carlyle features many of the same names we have talked about in previous editions of this series, which may come as no surprise to the reader. The Bush family and those around them are major players, with George H. W. Bush being a top advisor to Carlyle for years. The company was by and large a top landing spot for many retired intelligence and military officials, harkening back to the good old days of strong ties between Wall Street and the OSS.

One of Carlyle's first defense acquisitions, and the most important to the story within the context of the UFO cover-up, was of the technical services firm Braddock, Dunn, and McDonald (BDM). BDM provided consulting services for military and intelligence throughout the US defense agencies, mostly to the Army at first in the 1960s.

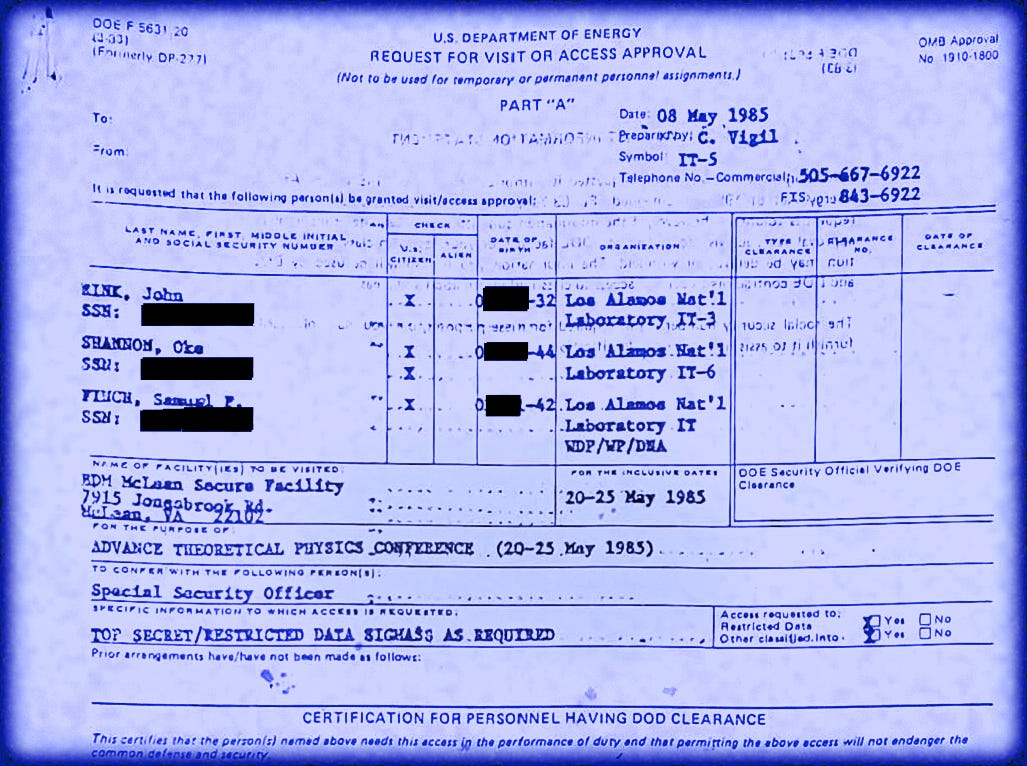

An interesting meeting happened at the BDM McLean secure facility in 1985 when what is known as the Advanced Theoretical Physics Working Group convened in a SCIF to create a plan for the study of the UFO phenomenon. Individuals present at the meeting included Hal Puthoff, John Alexander, Bert Stubblebine, Jack Houck, and many others with backgrounds in physics and aerospace engineering. When individuals hailing from corporations such as McDonnell Douglas, Lockheed, and Boeing meet with individuals who ran Project StarGate and the ice president of BDM, it's fair to say that the discussion around anomalous phenomena that took place was likely a very serious one.

Five years after this meeting about UFOs with top-tier aerospace engineers and BDM executives, BDM was acquired by Carlyle in 1990. Two years later, BDM purchased another company that may be represented in the Sekret Machines series as the private intelligence firm under Maynard's control.

1992, BDM acquired a company called Vinnell. Vinnell was a defense logistics firm with strong ties to Saudi Arabia, having signed their first contract with the country in 1975 where they were hired to train troops for the Saudi military.

Journalist Dan Briody describes the history of Vinnell in the context of their acquisition by BDM and Carlyle in his book The Iron Triangle: Inside the Secret World of the Carlyle Group.

In 1992, the time came to combine their newfound successes, when BDM, by then already under Carlyle's ownership, bought a little-known company of ambiguous ownership named Vinnell. The deal would marry Carlyle's burgeoning expertise in defense with its incipient relationships in the Middle East. And it would forever strengthen the political ties between two of the world's most powerful countries.

Vinnell is the clearest example of Carlyle's business inside the Iron Triangle. It combines all of the necessary elements of the military, government, and big business, in one neat, utterly secretive package. Vinnell defines the term war profiteer, a private company that trains foreign militaries in times of need, and would ultimately make Carlyle an insidious force inside the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia.

Vinnell is yet another company with a highly controversial past that Carlyle snapped up, only to heighten its questionable legacy. Vinnell's history, before, during, and after Carlyle owned it, is a litany of covert operations, mercenary missions, and cover-ups: right up Carlyle's alley. Carlyle, it seemed, was building an entire portfolio of controversy, and Vinnell was the early centerpiece.

One of Briody's sources, a former board member of Vinnell, describes what went on at the top of the company, hinting at a dynamic echoing theories of the breakaway civilization written about by Dolan and Farrell.

According to one former board member of Vinnell, who wishes to remain anonymous, Vinnell had been a cover for the CIA for decades. Dating all the way back to 1975, the company was gathering intelligence on behalf of the U.S. government, by infiltrating the Saudi National Guard under the specious guise of military trainers. The board member also says that though the company was supposed to be nothing more than a front for covert intelligence gathering, the darn thing started making money…

According to this board member, even after BDM purchased Vinnell in 1992, there was very little anyone on the board did in overseeing Vinnell. Board members met regularly, but rarely was anything acted upon. The company that seemed to run itself was, in fact, being run by someone else.

Vinnell sounds exactly like the intelligence service in Sekret Machines — and at the very least, demonstrates the shadowy nature of international banking and intelligence activity within a private investment firm with deep ties to the defense industry.

To be fair, the Maynard Consortium depicted in Sekret Machines as having reverse-engineered UFO technology could be any of a number of elite private equity firms. However, I personally believe the dynamic between Carlyle, BDM, and Vinnell — along with BDM's proven interest in the UFO phenomenon — makes them the most likely candidates.

Considering Vinnell was sold to TRW and is now part of Northrop Grumman, it's hard not to imagine what has happened in the years since.

Hopefully, we'll find out soon enough.

Excellent analysis, I think you are definitely on to something 👍

Really quite excellent. The SWIFT portion helped add definition to some sides. Is it possible someone has cheese somewhere in Ukraine?